Major Randolph Sabre, United States Army and Elaine Sabre, Arlington National Cemetery, VA

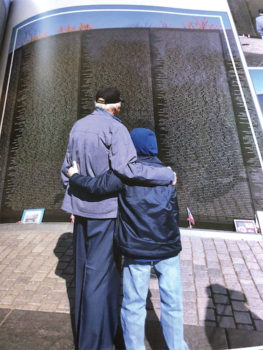

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Utzman, United States Army and grandson Hank, Vietnam War Memorial, Washington, D.C.

Corporal Sam Karr, United States Marine Corps

Bernadette Fideli

Imagine you are 18-19 years old. Senior Prom, beer-drinking pizza parties and beach scenes are gone. A helicopter just dropped you off on a mountain top in the middle of a jungle in a foreign country where people want to kill you. You are in Vietnam and you really don’t know why. You are sent on a recon mission into that jungle—the bush, as you learn to call it. You are weighed down with jungle gear; your vest alone weighs 18 pounds. The heat is oppressive, your only food is C rations in a container stamped with a 1942 date and you wear the same clothes for seven days. Ticks and leeches abound, you develop jungle rot and you march all day in the rain. At night, you man a listening post, awake, exhausted and in constant fear. Everything you have known is gone and you hope you make it home. Suddenly, from overhead, comes the whop-whop-whop sound of a Huey helicopter. It is the sound of hope, to carry you out of hell. Sam Karr knows well this feeling; he was on that mountain top. He will live another day.

You are a crew of four, flying a Huey, inside a thin aluminum helicopter with little to no protection. There are only two gunners, each with a machine gun, feet dangling over the Huey’s side, with no doors. You are a giant flying bullet magnet. There is no cover in the air and you frequently fly at altitudes well within range of enemy fire. You are the primary support, in fact the only support, and usually the only hope, for those troops on the ground. Sometimes you land into machine gun fire. Your Huey is hit; you are heavily on fire. Landing hard in the enemy jungle, you quickly jump from the burning Huey. The fire consumes your two weapons. Help cannot arrive for four hours. But you do make it back to base, alive, thanks to the Hueys and their crews. 4,901 pilots and crewmembers never did. Chuck Utzman and Randy Sabre know this; they flew the Hueys.

Vietnam is known as the “helicopter war” because the US relied almost entirely on helicopters to transport troops and provide gunship support. They became an absolute necessity in jungle warfare. A Huey can land on a clear patch of ground in the middle of the jungle. For the ground troops this meant ammunition and medical supplies, food, medevacking wounded, and reinforcements. Helicopter gunships provided life-saving fire on enemy positions with a precision and consistency that is not possible from a plane flying at hundreds of miles an hour. Helicopter pilots and crewmembers had but one mission: to support those on the ground. Ask a Huey pilot what gave him the most satisfaction and the answer is always the same: bringing a soldier home safely! On April 18, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, a long overdue monument was dedicated to those helicopter pilots and crewmembers who gave their lives for their brothers. Chuck and Randy, along with their wives, attended this ceremony. War creates bonds that transcend death, and the living never forget those that perished.